Whose bookshop is it anyway?

This morning I read a rather alarming article in The Bookseller about an independent, second-hand bookshop in Yorkshire that appears to be charging a 50p “admission fee” to those wishing to browse its shelves. I say “appears” because when asked to defend his actions, the shop’s owner claimed that he never took any admission money from customers, but rather meant this as a tongue-in-cheek remark to see if people were genuinely interested in buying books and taking the business seriously.

Whatever the truth may be, I don’t know what’s more shocking: the idea of a bookshop charging admission, or the fact that customers supposedly have to prove that they’re “serious about books.”

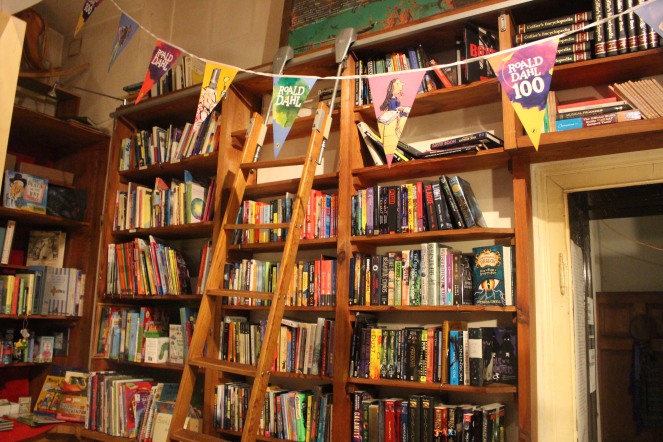

Whether you’re an avid bookworm or a more reluctant reader, you should always be welcome in a bookshop. Bookshops are supposed to be safe havens and places to discover the secrets of the universe. The number one reason I love books is because they are a way to understand a perspective different from your own. They teach compassion. They are weapons in the fight against the pandemic of ignorance that, more than ever, is infecting our political systems. I’m not saying that books are the best or only way to educate the masses. After all, there are many who don’t have access to books. The ability to read is a privilege in itself, before we even take into account the socio-economic factors that may deter people from picking up a book (more on that later). However, denying someone access to that education is enraging. Implying that some people are not worthy of accessing it is even worse. It makes me want to smash something.

In my job as a bookseller, I’ve encountered plenty of people who feels nervous about visiting a bookshop, and even more who feel shy asking us for help. These are the people to whom we should reach out, rather than pushing them away with the elitism exhibited by the aforementioned shop. Some of my most rewarding moments at work are when people approach me and admit that they don’t read much and need some help picking up books that will get them into the habit. Customers like this have no preconceptions about what “literature” should or should not be, and are often willing to take risks. After all, it takes an enormous amount of trust and vulnerability to rely on a bookseller who doesn’t really have much information about you, and who has to make snap decisions about what you might like. It’s a two-way relationship: the customer trusts and respects the bookseller’s knowledge, but the bookseller must be sensitive to the customer’s needs and really think hard in order to put the perfect book in their hands. It’s simply not enough to simply go into autopilot and chuck the latest bestseller at them. After all, our Alien Overlord Amazon could do that. There’s a reason John Green once said “You cannot invent an algorithm that is as good at recommending books as a good bookseller.”

One of my stand-out moments at work – for both positive and negative reasons – was when a group of students from a high school in an economically deprived came to visit the shop. For the past few years, this school has received a grant to enable students to choose new books for their library. I’d handled school visits before, but this was by far the most rewarding. One of my colleagues filled me in on the situation: while many of the students at the school enjoy reading, financial strain mean that they can’t always afford to buy their own books. Their families must prioritise other things. On top of that, visiting a bookshop requires paying for buses in and out of the city centre, and many of them are intimidated by the idea of browsing a bookshop. They fear that, as working class teenagers, they may not be respected by other customers and members of staff. Perhaps they’re worried that they won’t come across as “serious about books” (beginning to sound familiar?).

Now, staff-wise, I have never met – or at least worked with – a single bookseller who would look down on these students. On the whole, we’re a friendly, tolerant, respectful bunch who want to see everyone find a book that suits them. We recognise that bookshops are places of self-growth, and that browsing and thinking and engaging with books – and thus tiny pieces of the world around us – is to be encouraged. Other customers are often less kind. I recall one elderly woman who, upon witnessing this particular school group having fun (calm fun, might I add, little more than chatting loudly about what books they were choosing) in the shop, stormed up to me and proceeded to have a rant that went a little bit like this:

Woman: “what are all these brats doing here? Shouldn’t they be in school?”

Me: “it’s a school trip. They’re choosing books for their school library.”

Woman: “well, they’re being incredibly rude. So loud, running around, acting like little brats. It totally ruins it for the rest of us.”

Me: “actually, we’re really happy they’re here. They’re from quite a deprived area and don’t really have access to bookshops, so it’s a real privilege for them to choose their own books.”

Woman: “I don’t see how I can enjoy looking at books or having a coffee with them screaming all the time. makes purchase and turns to leave Remind me to never come back here for coffee!”

Me: “okaybye.”

The sad truth seems to be that many believe there are still certain groups of people that should be denied access to books. The ironic thing is that if you spoke to those perpetuating this damage and addressed this issue head-on, they would most likely deny being part of the problem. These harmful attitudes are so deeply engrained that many don’t even realise that they are part of the problem.

In a certain light, it’s good that this story has made the news. While book snobbery is never cool, perhaps this is the push we need to start the conversation about how we, as a society, have created unnecessary barriers to knowledge, independent thought and compassion. There are so many cultures where certain demographics (primarily girls) are denied an education, and so many of us are quick to criticise the inequality here. In the western world, we are largely privileged enough to access education in basic literacy so it’s not directly comparable, but if we begin stereotyping people and putting them into boxes of who “should” or “should not” read, “should” or “should not” be allowed in a bookshop, we’re creating an educational inequality of our own. It’s undeniably insidious.

Bookshops are for everyone. Let’s stop letting literary elitists monopolise them.